Mass protests across Kenya are exposing deep public anger toward President William Ruto just three years into his five-year term. Once seen as a champion of the working class, Ruto is now facing growing opposition, especially from young Kenyans who feel betrayed by his policies.

Chants of “WANTAM,” meaning “one-term president,” are heard in the streets. Demonstrators raise their index fingers, calling for Ruto to step down in 2027—or sooner. Some want him out immediately, blaming him for economic hardship and growing repression.

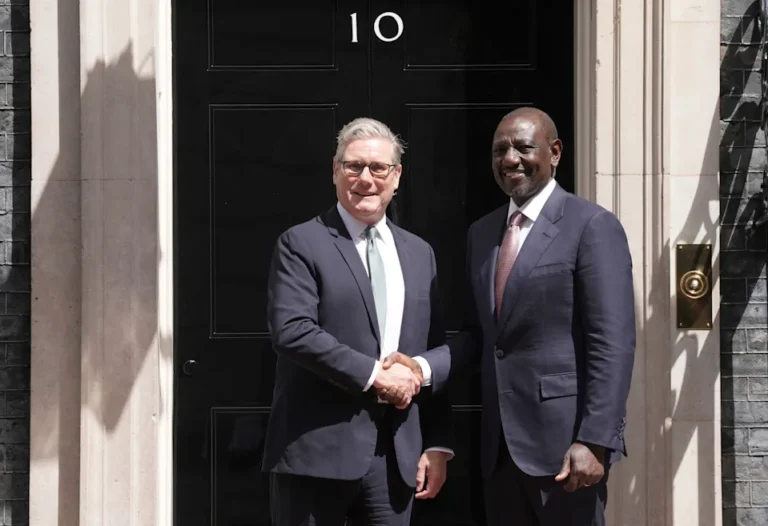

Ruto, who took office in 2022, lost support after introducing new tax laws that many see as unfair to ordinary people. The president defended the taxes as necessary to fund the government. But critics say they break his promises to help low-income families.

Last year, protests against these tax hikes turned deadly. At least 22 people were killed when crowds tried to storm parliament in Nairobi. Although the government stopped the unrest, the anger didn’t disappear. A fresh wave of protests began recently after a popular blogger died in police custody.

The death triggered public outrage and renewed criticism of Ruto’s control over Kenya’s institutions, including the police and lawmakers. Analysts say he has power, but not the people’s trust. One expert described him as possibly the most disliked president in Kenya’s history.

While Ruto is expected to remain in office until 2027, experts warn the unrest may grow. Many protesters are calling not only for his exit but for wide reforms to remove corruption and improve governance.

Demonstrators often refer to Ruto as “Zakayo,” comparing him to a biblical tax collector. Others use the Kiswahili word “mwizi,” or “thief,” to describe him. These labels reflect public frustration over government spending and the lavish lifestyles of politicians.

One deal, in particular, added fuel to the fire. A $2 billion airport agreement with India’s Adani Group was scrapped after public outcry. The news came months after the tax protests were violently suppressed. Many saw the move as another example of poor leadership.

Ruto’s focus on expanding the tax base has also stirred resentment. His talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have raised fears that economic reforms will hit the poor the hardest. Critics argue that only the wealthy and politically connected stand to benefit.

Speaking to Harvard Business School last year, Ruto said he would not lead a “bankrupt country.” But back home, many feel he is not listening. A Kenya-based analyst said the grief and anger from last year’s protests remain strong.

Young Kenyans are at the forefront of this movement. Student Peter Kairu, 21, said he has little hope the government will fight corruption or nepotism. He believes lasting change must come from the people.

Others fear for their safety. Eileen Muga, an unemployed woman in Nairobi, said people risk disappearing if they speak out. Still, thousands marched again last week, marking the anniversary of the anti-tax protests.

In response, Ruto gave a speech warning that the protests could tear the country apart. He said Kenya does not belong to him alone, but if there is no country for him, then there is no country for anyone.

This hardline stance reflects why many are afraid of Ruto, even as they demand change. His interior minister has promised to crack down on protests with force.

Ruto has a long history of political battles. As deputy president, he clashed with his former boss, Uhuru Kenyatta, and later defeated opposition leader Raila Odinga in a tight election. He then brought Odinga closer, weakening any serious challenge in the next vote.

More recently, Ruto’s relationship with his own deputy, Rigathi Gachagua, collapsed. Parliament moved to impeach Gachagua, though Ruto denied involvement. Observers saw this as yet another sign of his intolerance.

Ruto rose to power by promoting himself as a man of the people. He branded his campaign as the “hustler nation,” appealing to market traders, motorbike drivers, and small business owners. He also aligned himself with evangelical Christians, often preaching in churches with a Bible in hand.

But after taking office, Ruto quickly changed course. He removed fuel subsidies and pushed through a finance bill that raised taxes—moves that hurt many of his supporters.

According to political analyst Eric Nakhurenya, the problem lies in making too many promises and not delivering. For many Kenyans, this gap between words and actions is the root of their frustration.