Mention the names of Mrs. Wuraola Esan, Chief Margaret Ekpo, Janet Mokelu, Ekpo Young, and Hajia Gambo Sawaba, and they echo through Nigeria’s political history. These women paved the way for future generations, even in the face of serious challenges.

Mrs. Esan made history in 1961 as the first woman to enter the Federal Parliament. Margaret Ekpo was elected to the Eastern Nigeria House of Assembly, also in 1961, and served until 1966. Janet Mokelu and Ekpo Young also made strides by securing seats in the same regional house. Gambo Sawaba, though a strong activist and voice for the poor and women, was never allowed to vote or contest elections because she came from Nigeria’s northern region. At the time, that region barred women from full political participation.

This lack of access highlights the long road Nigerian women still face when trying to claim their place in politics. Despite the Beijing World Conference on Women advocating for 30% political inclusion, and Nigeria’s own National Gender Policy pushing for 35%, real progress has been slow.

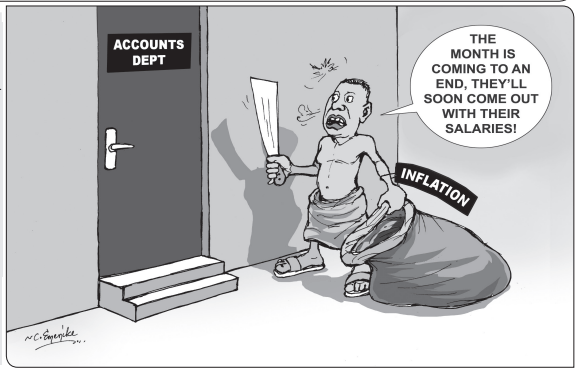

Today, the national average for women in elective and appointed roles is only 6.7%. This is far behind the global average of 23.4% and West Africa’s regional average of 15%. In 2015, just six out of 36 ministers were women—only 16.7%. From 1999 to 2015, women made up only 5.6% of the House of Representatives and 6.5% of the Senate.

This situation is not just about numbers. It speaks to the value placed on women in a democratic system. Nigerian democracy cannot truly succeed while half the population is underrepresented. Women’s voices are needed to ensure justice and equity in national decision-making.

Beyond politics, Nigerian women still suffer deeply from harmful traditions. Practices such as female genital mutilation, child marriage, and domestic violence continue in many areas. Some women are even denied inheritance rights and forced into single motherhood without support. With more women in political power, there would be stronger efforts to fight these abuses and improve the lives of millions.

Sadly, history shows how few women have held real power. During Nigeria’s Second Republic (1979–1983), only one woman, Franca Afegbua, was elected to the Senate. Only one female Permanent Secretary—Francisca Yetunde Emmanuel—served during that time. There were just two women in federal ministerial roles: Janet Akinrinade and Adenike Ebun Oyagbola.

Since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, no woman has ever been elected as a state governor. This stands in stark contrast to several other African nations. Burundi, South Africa, Liberia, Gabon, Malawi, Ethiopia, and Tanzania have all had female presidents or acting heads of state. Tanzania’s current president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, has led an agricultural revolution that increased food security by 250% and boosted exports.

Zambia recently made history by electing its first female president, Tasila Lungu, along with a female vice president. These women are reshaping politics across Africa.

Back in Nigeria, Senator Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan has shown what female leadership can look like. Representing Kogi Central, she has made headlines for speaking out against sexual harassment allegations involving the Senate President. Beyond that, she has delivered real change in education, healthcare, infrastructure, and poverty relief.

Her performance shows what Nigeria could gain from allowing more women into positions of power. They bring fresh ideas, bold actions, and often, a strong connection to the grassroots issues people care about most.

The demand for more women in Nigerian politics is not just a gender issue. It is a national development issue. When women lead, communities benefit. Nigeria cannot afford to ignore half its population any longer. The time for change is now.